This week is International Compost Awareness Week and we’ll be bringing you lots of great tips and inspiration for starting or growing your compost pile. we’ll also share why simply diverting your food scraps from the landfill is a good idea.

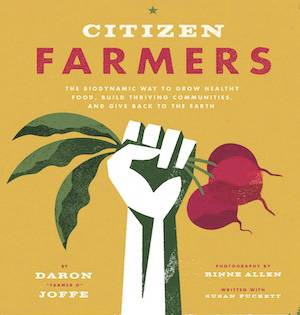

Citizen Farmer’s author Daron ‘Farmer D’ Joffe was recently featured on the Mother Nature Network talking about what else but composting and his passion for community agriculture. Here’s the full article:

Farmer D and the Tao of Composting (reposted from MNN)

All photos: Rinne Allen

In his new book “Citizen Farmers,” Daron “Farmer D” Joffe positions farming as both a sustainable and a philosophical lifestyle, merging helpful how-to’s with spiritual underpinnings. In this excerpt from the book, Joffe discusses how he came to learn about composting, and how it encourages stewardship of Earth.

Composting = Stewardship

Every successful venture begins with a healthy foundation. Before we can grow food, we have to grow soil — and lots of it. I make good dirt for a living. I also make it at home, every day, beginning in the morning when I toss the grounds from my coffee and the banana peel from my smoothie into the compost caddy by the sink.

When it’s full, I dump it into the backyard compost bin. Over a period of weeks and months, billions of bugs, bacteria, and fungi will convert these stinky, rotten kitchen scraps mixed with yard debris into fertile, sweet smelling, life-giving earth.

Soil is the skin around our earth and the source of our sustenance, where life starts and finishes. Yet most of us take this vital resource for granted. Much of our earth has been degraded, overfarmed, and undernourished for many decades. We are currently losing topsoil faster than we can regenerate it. Millions of tons of organic materials that could be composted are taking up valuable space in landfills, rather than being returned to farms to grow healthy food.

Replenishing soil is just one of the many positive outcomes of composting. This practice can also drastically reduce, if not eliminate, the need for petroleum-based fertilizers, which pollute soil, air, water, animals, and humans. Compost builds the organic matter in soil, which helps plants grow strong and increase resistance to pests, disease, and drought.

Composting is a daily reminder of our individual tasks as citizen farmers: contributing to a healthy planet and being a responsible steward of the land. In this chapter, I hope to inspire you to make composting as essential to your daily routine as brushing your teeth. I want to share with you some very important tips on how to make your soil thrive so the food you grow helps you to thrive, too.

Love at first scoop

Until college, I never thought twice about tossing table scraps anywhere other than in a trash can or down a garbage disposal. It was shortly after my turkey sandwich revelation when someone I met at a party told me about an introductory workshop on biodynamic farming that was coming up at the Michael Fields Institute, about an hour from Madison, Wisc. Founded in 1984, this nonprofit organization is one of the cornerstones of the biodynamic movement in the United States, with the mission of promoting sustainable agriculture through education, research, and outreach. There, I studied under several composting gurus who changed the way I thought about “dirt” forever.

Under their guidance, about a dozen farming newbies, including myself, learned how to build a biodynamic compost pile with garden refuse, dairy manure, spent hay, and a little soil from the garden. We spent a grueling day shoveling and spreading layers of this organic matter as if making a monster-size batch of lasagna.

As the pile grew taller, we leaned a huge wooden board against the pile so we could run the wheelbarrow up to dump more materials on top. By the end of the day, our pile had grown to the size of a pickup truck. We covered it all with a layer of straw and doused it heavily with water, using a hose with a shower nozzle to replicate falling rain. Then we put holes in the pile at the locations specified in the biodynamic agriculture lectures by Rudolf Steiner, and added the requisite biodynamic compost preparations. the workshop was over, and now it was time to let Mother Nature work her magic.

I had dipped my toe into biodynamic farming and was now officially on my way to becoming a true citizen farmer.

Down the rabbit hole

Back at school, I scoured a list of local organic farms put out by the university’s agriculture school and started calling them to see which ones offered apprenticeships.

Then I met Greg David, a former commercial builder turned organic farmer who occupied a bubble of biodiversity in the midst of an endless, sterile monoculture of corn crops about forty-five minutes from Madison. Greg hired me, and for the next six months I rose at the crack of dawn every day to drive from Madison to Greg’s farm to work until dark — for fifty bucks a week.

Greg was especially passionate about restoring what had been a monoculture field of corn into a vibrant native prairie in order to create a sanctuary for wildlife in this agricultural desert. I helped him do this by preparing the ground and seeding it with a nurse crop of sunflowers that would provide shade and eclipse the weeds. Once the prairie was established, we would burn it periodically to maintain the revitalized soil. Greg also had cutting-edge ideas about composting. He formed a relationship with the Department of Natural Resources and they would bring him truckload after truckload of fallen leaves and mucked-up lake weeds that would get dumped on the farm into long windrows. He was essentially harvesting all the organic matter from the region, composting it, and building up the soil fertility of his farm.

Once the mountains of leaves and lake weeds reached a certain size, he would fence his fifteen or twenty Tamworth pigs in around these piles. One of my jobs was to walk across each pile with a can of dried corn kernels and a shovel handle, and every 10 feet or so make a 3-foot-deep hole and drop a handful of corn down it. The pigs would root for the corn, and turn the compost in the process. When the pigs weren’t being used to turn the piles, we would set them out to plow the fields by uprooting and eating the quack grass, which they could do better than any tractor. Not only did the pigs completely clean the fields of this pervasive weed, but they simultaneously fertilized the fields, saving us from driving the tractor all over them, compacting the soil, and burning fossil fuels.

I have a memory of walking the compost piles in the rain, collecting a bumper crop of the most beautiful volunteer tomatoes, peppers, and squash—plants that had sprouted voluntarily from the seeds of rotting fruit that had been turned by the pigs in this unbelievably fertile compost pile. I had never before seen composting in action on that scale, and it was revelatory. This was biodynamic farming at its best, where animals were integrated into the agricultural organism in a humane and productive fashion, and the spoils of fallen leaves and rotting vegetables could be transformed into fertility for the land and an abundant harvest of food for the CSA.

Biodynamics: A vehicle for action

Armed with the basic tools for becoming an organic farmer, I was beginning to see a career path for myself that did not involve academia. After my awe-inspiring internship with Greg, I decided to withdraw from school and take on another apprenticeship instead, this time on a full-blown biodynamic farm in the North Georgia Mountains, run by Hugh Lovel.

Armed with the basic tools for becoming an organic farmer, I was beginning to see a career path for myself that did not involve academia. After my awe-inspiring internship with Greg, I decided to withdraw from school and take on another apprenticeship instead, this time on a full-blown biodynamic farm in the North Georgia Mountains, run by Hugh Lovel.

Hugh had been farming this valley for more than twenty years and had turned a rocky creek bottom into one of the most fertile farms in the country — with compost, biodynamics, cover crops, and permanent grass and clover pathways between his vegetable beds. In the spirit of a true biodynamic farmer, Hugh produced everything he needed to sustain himself on his land, and I tried to follow in his footsteps. I managed the farm for most of my time there; I learned how to hand-milk cows and goats, make cheese and yogurt, grow rice, raise pigs, pickle okra, and save seeds. Hugh showed me how to build doughnut-shaped compost piles with manure and bedding from the animals. Compost from chickens would go to fruiting crops; cows, to leafy greens; goats, to herbs and flowers; pigs, to potatoes. I learned about radionics: influencing energetics through frequencies.

Prep making, planting with the moon, stirring, spraying, and sharing knowledge with others are some of the actions that biodynamic farmers take to make their farms and communities thrive. While many of these techniques may seem pretty unorthodox, one thing that is very clear is that the farmer’s intention is the key to a well-managed farm. The goal is to be a good steward and leave the earth in better shape than we find it. Through Hugh, I became convinced that biodynamics provides a handful of very powerful tools for doing this and, at the same time, gives the citizen farmer’s intention a vehicle for action.

Compost meditation: Compost for the soul

I have learned that, when applied metaphorically, composting can help us thrive in any environment we are planted in—be it the boardroom, classroom, or family dinner table. When building a compost pile, I like to turn the rhythm of shoveling into an internal meditation that allows me to compost negative thoughts into positive ones: fear into faith, judgment into compassion, insecurity into confidence, and anger into love.

I have learned that, when applied metaphorically, composting can help us thrive in any environment we are planted in—be it the boardroom, classroom, or family dinner table. When building a compost pile, I like to turn the rhythm of shoveling into an internal meditation that allows me to compost negative thoughts into positive ones: fear into faith, judgment into compassion, insecurity into confidence, and anger into love.

Composting for the soil is the process of breaking down organic materials, while composting for the soul is the process of breaking down personal struggles (grudges, frustration, stress, anger). You bring the problems to the surface, add the good stuff to the heap (honesty, communication, support, nurturing), and give it time to “cook.”

Building a compost pile is a meditation unto itself. Identify the location for the new pile by scratching a circle or square to mark the periphery. Loosen up the soil with a digging fork and add a sprinkling of lime, ash, and blood meal. As you build the pile, let your mind go and just tune into the rhythm of shoveling back and forth. It is an active meditation that results in a radiant pile of decomposing organic matter.

Even after this compost meditation is over, I use composting imagery frequently to dispel the mental clutter that may be holding me back in areas of my life beyond the garden. It has helped me make peace with business partners I’ve fallen out with, move on from stagnant relationships, remove obstacles impeding the creative process, and replace stress and anxiety with joy and gratitude—just like composting turns stinky raw manure and rotten vegetables into rich, sweet-smelling, fertile soil.

As the old Chinese proverb goes, a bad farmer grows weeds, a good farmer grows crops, and a great farmer grows soil. Be a great citizen farmer and make compost for a better life and a healthier planet!

“Citizen Farmers” by Daron Joffe with Susan Puckett is available for purchase from the following online retailers: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Abrams, and IndieBound.

0 COMMENTS